The statements, views and opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of this site. This site does not give financial, investment or medical advice.

Originally appeared on NICHOLAS KOTAR

Everywhere you look these days in the entertainment world, you see superheroes. And although we may (finally) be getting to a state of “superhero fatigue,” it won’t last long. The idea of the superman, the perfect hero, has always fascinated people. In Russian culture, the role of the superman is played by the great warrior, the bogatyr.

My own novels play with the idea of the bogatyr as protector of the land. But rather than just having this superhuman guy beat up on bad guys all the time, I follow the old Russian models in exploring the failings, the humanness, of these superhuman warriors.

I’ve already written a bit about the historical models for three bogatyrs. Today, I found an article about the seven most famous heroes of Russian epic poetry (click the link for the original Russian article). As usual, at least some of the details I share with you will make their way into my novels.

Pretty much all Russians know the names of the famous “three warriors”—Ilya Muromets, Alesha Popovich, and Dobrynia Nikitich. But they weren’t the only ones. Let’s also explore some of their lesser known brethren.

Where did bogatyrs come from? The epic poems of their exploits, part of Russia’s rich oral tradition, were first written down in the 19th century. Before that, they were passed on, usually from grandfather to grandson. Each storyteller had his own version of the tales.

Generally, historians recognize two categories of these tales—the “elder” tales and the “younger” tales. The elder tales are ancient, belonging to the pre-Christian period. In these tales, the bogatyrs are basically gods, warriors, or even shape-shifters with superhuman strength.

The “younger” bogatyrs, though they are very strong, are human. Nearly all of them live in that half-legendary time of Kievan Rus when Prince Vladimir reigned (980-1015). This and many other details from the chronicles suggest that most of the events that became legendary did have their historical origins.

- Sviatogor—the Giant Warrior

A terrifying giant, the oldest of the “young” bogatyrs, Sviatogor is as large as a mountain. In most of the tales, he has grown so huge that the earth can no longer hold him, and he lies half-buried, waiting for death. There are reasons to believe that Sviatogor is a Russianization of the Biblical Sampson, although it’s difficult to determine exactly what his origins are. His most important purpose in the stories is to pass on the ancient power of the “old” bogatyrs to the most popular representative of the new—Ilya Muromets.

In my new novel, The Garden in the Heart of the World, the warrior-giant comes alive in a race of warriors who belong to the old order of the world, the order of earth-magic. Essentially, they are the pagan holdovers in a land that is quickly learning to become monotheistic.

- Mikula Selianinovich

We find him in two epic poems, one with Sviatogor, and another with Volga Sviatoslavich. Mikula is remarkable not so much for his strength as for his limitless endurance. He is the first peasant bogatyr, a great warrior-ploughman. His great endurance, together with Sviatogor’s titanic strength, indicate that their story probably came from old myths about the god of the earth and the patron-god of farmers. But if Sviatogor is a representative of the old, “mythic” world, Mikula is personification of the beauty of the farming lifestyle, into which he pours his considerable strength.

- Ilya Muromets

Ilya Muromets is the most important protector of the Russian land against enemies (most of whom were nomadic Asian tribes that harassed Rus for centuries). Although he is definitely a historical character, his story is still mythical. He sat paralyzed for thirty years, then received his power from Sviatogor directly. He captured Nightingale the Robber, then freed Chernigov from the Tatars. And that’s only the beginning of his story.

In addition to his physical strength, he has remarkably strong morals. He is calm, firm, simple, non-acquisitive, fatherly, restrained, generous, independent. Even so, he has a temper that sometimes gets the better of him. In one famous story, he gets angry at Prince Vladimir and retaliates by knocking the crosses off of St. Sophia Cathedral with an arrow. After a while, his character’s religiosity began to take center stage (maybe he felt the need to atone for knocking off the crosses from the cupola?) He did, eventually, become canonized as a monk-saint.

The probably history of Ilya Muromets is something like this. After many years of being a great warrior, he was seriously wounded. So he decided to change his sword of metal to a spiritual sword, and became a monk in the Kiev Caves Lavra. This is a traditional end for a Russian warrior—to live his days in battling physical enemies, but to end them in spiritual warfare.

This aspect of Ilya Muromets is something that fascinates me personally. My own “bogatyr” character in my novels, Voran son of Otchigen, follows that traditional trajectory from warrior to monk.

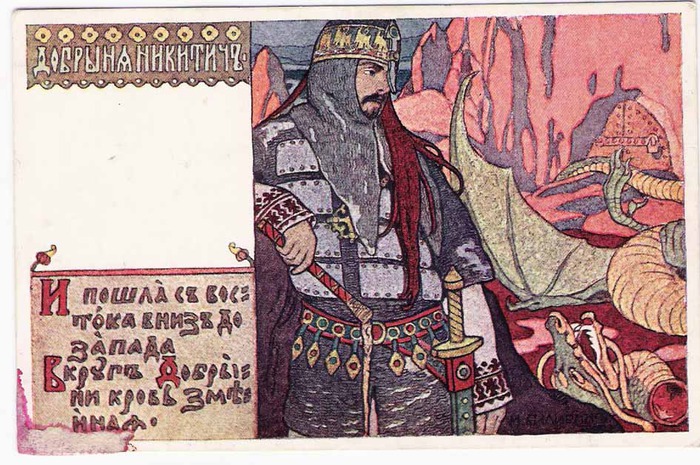

- Dobrynia Nikitich

He is the bogatyr with the lion’s heart. Even his name indicates his gentle heart. Though he has great physical strength, he “will never insult a fly,” he is “the protector of the widows and the orphans, and of all damsels in distress.” Dobrynia is also an artist at heart—he has a beautiful singing voice and plays the gusli (Russian harp). He is also one of the old noble-born bogatyrs, a model of the prince who is also master of the druzhina (warrior band). He also knows manners and etiquette very well.

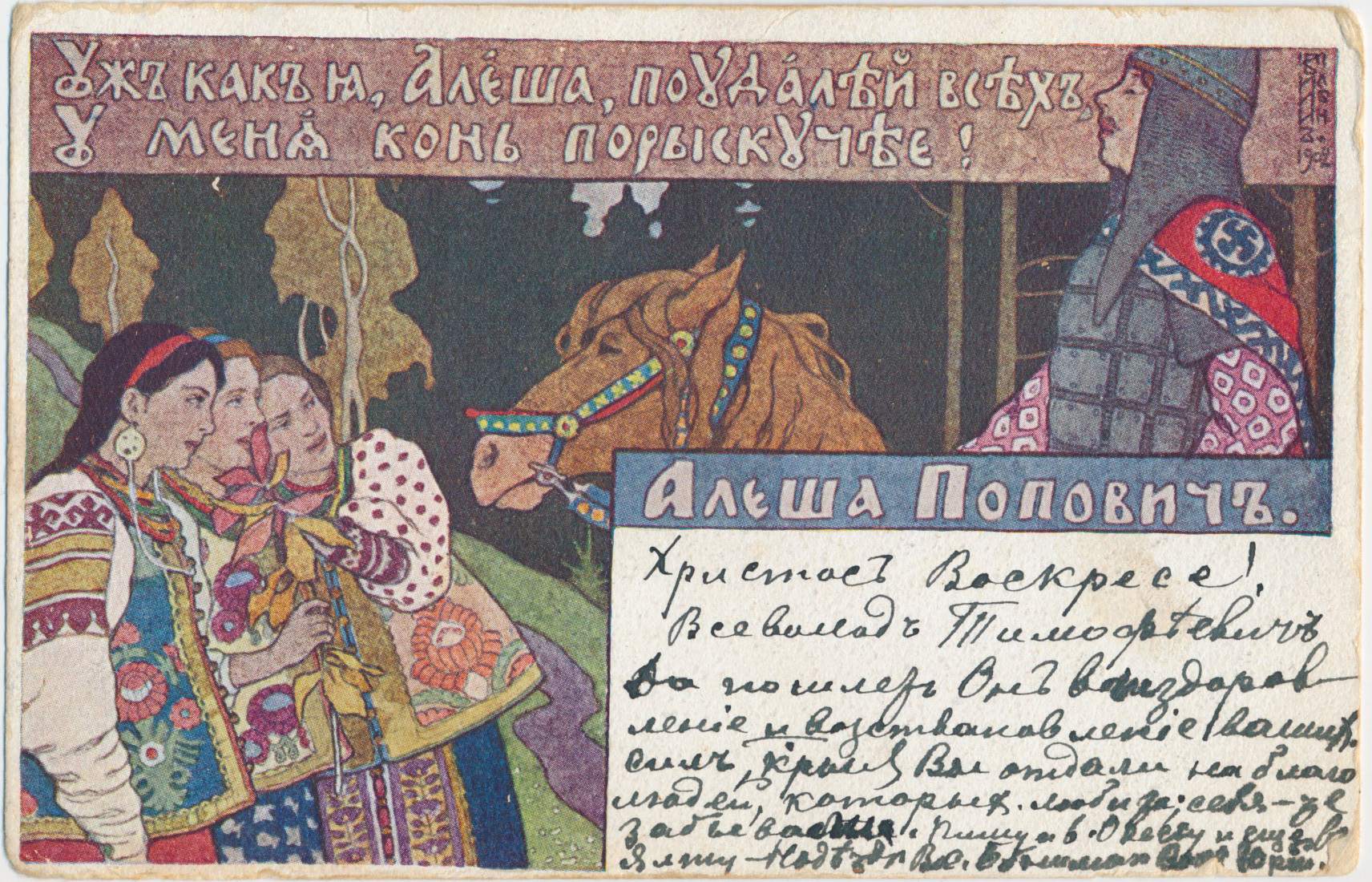

- Alyosha Popovich

He’s often connected in the popular imagination with Ilya Muromets and Dobrynia Nikitich. He is, as it were, the youngest of the “young” bogatyrs, and so is not quite as much a superman as the rest of them. He is cunning, egotistical, and likes to make money for himself.

So, on the one hand, he is remarkably bold and courageous. On the other, he is proud, meddlesome, crude. He likes to provoke people and is easily angered. Ultimately, he becomes a slave of his shortcomings. In particular, if Dobrynia is a protector of women, Alyosha tends to take advantage of them, though he is never a particularly successful lover.

Of all the bogatyrs, he ends up the most pitiful.

- Mikhailo Potyk

One of the lesser known warriors, he fights the serpent of evil, the Biblical enemy of all mankind. Of all the bogatyrs, he is perhaps the only one that may be associated with hagiographic literature (there was a Bulgarian saint, Michael from Potuka, who was one of many warrior-saints to have battled a serpent and won).

He is a restless man, a wanderer and a pilgrim. It’s possible that his name was originally “potok,” which in the old Russian means “landless” or “nomadic.” In some ways he is an idealized pilgrim, an image that holds an important place in the Russian imagination. There is also a version of the tale written by Alexei Tolstoi that imagines Mikhailo as a time-traveling warrior.

In my own first novel, A Lamentation of Sirin, the Pilgrim-wanderer is almost an institution, someone who is given great honor when he visits. One of them ends up being much more than any of the other characters in my novel expect.

- Churila Plenkovich

He is a mercenary bogatyr. Other than the “elder” and “younger” bogatyrs, there’s another category of supermen that were “out-of-towners” or mercenaries. Churila is one of these. Their names always indicate the place they come from. In the case of Plenkovich, he comes from Surozh, on the Crimean Peninsula. Unlike nearly all other bogatyrs, Churila is a fop, an old Russian Don Juan. The tales describe him as having “skin like snow, eyes like a falcon’s, eyebrows black as sable.” To keep his complexion pleasingly pale, he actually has a servant following him around with a parasol, to protect him against the sun.

The famous Russian critic Vissarion Belinski noted that Churilo was the most “humane” of all the “young” bogatyrs, especially with respect to women. It seems he has dedicated his life to them. He never utters a single crude word or expression. On the contrary, he acts in some ways like the traditional knight of the Western troubadour tradition.

Women-storytellers preferred his tales to nearly all others.

The statements, views and opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of this site. This site does not give financial, investment or medical advice.